10 Things You Didn't Know About the NYC Subway

- wander woman

- Sep 17, 2018

- 7 min read

Here are ten of my favorite obscure facts about the New York City subway system. Enjoy!

1. There were once cars reserved only for women

In March 1909, women-only subway cars, known as “suffragette cars” were introduced on trains running from Manhattan to Hoboken (today’s PATH train). During rush hour, the last car in each train was reserved exclusively for women and children. Unsurprisingly, the proposal prompted a passionate public debate, which played out for months in Letters to the Editor of The New York Times:

While the initiative was lauded by some women’s groups like The Women’s Municipal League, it was vehemently opposed by many others for being impractical, unnecessary, and undesirable. As a result, the plan was ultimately abandoned several months later.

2. The oldest subway tunnel in the world is in Brooklyn

In 1844, the Atlantic Avenue tunnel was built as part of the Long Island Railroad, a commuter rail line that connected New York to Boston. The subterranean tunnel predated the London Underground system (1863), the Tremont Street subway in Boston (1869), and New York City’s first official subway, a 312-foot pneumatic powered line that operated from 1870 to 1873.

The tunnel ran for a half-mile under Atlantic Avenue in downtown Brooklyn. The tracks were placed underground to avoid deadly collisions with pedestrians or livestock. At the time, trains had bad breaks and accidents were common in densely populated neighborhoods.

In 1861, the tunnel was closed and the existence of the world’s first subway was quickly forgotten. In 1896, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote that “The Long Island railroad tunnel is something of a mystery. Comparatively few people in Brooklyn known that such a thing exists, where it is, when it was built, to what use it has or has been put, who owns it, and what is likely to become of it.” The tunnel was rediscovered in the 1980s by an urban explorer named Bob Diamond. New York City sealed off the entrance to the tunnel in 2010, but subway geeks can still get inside the tunnel’s old coal room. The historic space is now part of Le Boudoir, the speakeasy below the Chez Moi restaurant at 135 Atlantic Avenue. Fortunately, the owners preserved many of the original details, including the coal hole on the ceiling and the coal stains on the walls.

3. There is a secret library located inside the 51st Street/Lexington Ave station

The Terence Cardinal Cooke-Cathedral branch of the New York Public Library is located just outside of the turnstile for the 6 train on the corner of Lex and 50th Street. It has no street-level entrance or sign. The branch opened in 1992, but the 2,100 square-foot space has housed a library since 1887. According to the branch manager, many commuters confuse the NYPL for a MTA help desk. “They come in asking for help with the MetroCard machine,” she told the New York Times in 2010. “We do help them if we’re not too busy, and they also ask us for subway maps, so we keep a lot of them on hand.”

Interestingly, the NYPL was not the first library to have a direct entrance to the subway. From 1854 to 1932, the Mercantile Library of New York was located at 21 Astor Place. In it’s heyday, the library, which was known as Clinton Hall, had 12,000 members and over 120,000 volumes, making it the largest circulating library in the country at the time. Famous figures such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Mark Twain, and Frederick Douglass held lectures there. It was such a significant building that when the Astor Place station was built in 1904, a direct entrance was constructed for Clinton Hall. The Mercantile Library relocated to 47th Street in 1932 and the building’s subway entrance was boarded up. All that remains is a plaque hovering over a subway map outside the turnstiles on the downtown platform.

4. New Yorkers used to suck tokens out of turnstiles

Before the advent of MetroCards, rides were paid for with subway tokens. When they became extinct, so too, did an innovative albeit disgusting crime: token sucking. The thief would jam the token slot with a piece of paper and wait for a commuter to try to insert a token. Afterwards, the thief would place his or her lips over the jammed slot and suck out the token. While unimaginable today, in the late 1980s, token sucking was apparently an epidemic. According to the New York Times, during the summer of 1989, “repair crews were sent on 1,779 calls to fix turnstiles in a system that had 2,897 turnstiles in all. More than 60 percent of the calls involved paper stuffed into the token slots.” Some token booth clerks resorted to sprinkling chili powder or mace outside of the token slots.

5. There is a MTA Signal Training School hidden inside of the 14th Street A/C/E Station

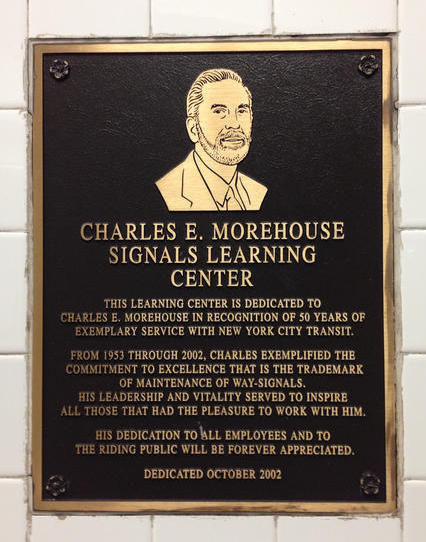

The majority of the subway lines are still manually operated, meaning that a human controls whether trains are re-routed to another track and changes the signals from red, yellow, and green between each station. The antiquated signaling system is one of the major causes of delays and long wait times between trains. Eventually, the MTA is hoping to transition all lines to a computerized control system, but since the initiative was announced in 1991, only the 7 and L lines have been outfitted with modern signaling equipment. Subway workers take a 18-month training course to learn how to change the signals and operate the equipment, much of which dates back to the 1930s. Where do they do all of this? At the Charles E. Morehouse Signals Learning Center hidden inside the A/C/E 14th Street Station! According to a plaque, from 1953 to 2002, Charles “exemplified the commitment to excellence that is the trademark of maintenance of way-signals.”

6. A massive subway map is embedded on a sidewalk in SoHo

A stainless steel model of the Manhattan subway map is embedded in the sidewalk outside of 110 Greene Street. The map is 90 feet long and 12 feet wide. It was installed in 1985 by Françoise Schein, a Belgian artist and architect, who moved to New York in 1978 to study Urban Design at Columbia. “The subway fascinated me,” Schien wrote in her project notes. “its filth, its life, its graffiti, the millions of travelers who used it everyday like milling ants or electrons in a computer…” The piece, entitled Subway Map Floating on a New York City Sidewalk, earned Schien the 1985 Award for Excellence in Design.

7. The Hoyt-Schermerhorn subway station was featured in a famous music video

In addition to the A, C, and G lines, the Hoyt-Schermerhorn subway station was once home to the HH shuttle, which connected to nearby Court Street. The MTA discontinued the shuttle in 1946, but never repurposed the station’s extra platforms.

Over the years, film crews have repeatedly capitalized on this unused space. Most famously, the abandoned HH shuttle platform was the backdrop of Michael Jackson’s iconic “Bad” music video, directed by Martin Scorsese.

8. But that’s not all! The Hoyt-Schermerhorn station is also home to the remains of a lost department store.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Fulton Street was home to many famous department or “dry good” stores. One of the few remaining traces of this history can be found inside the Hoyt-Schermerhorn station. The mezzanine hallway is decorated with large blue and yellow tiles with a prominent “L” encircled in the middle. The tiles are a reference to Loeser’s Department Store, which once had a direct entrance into the subway. In fact, the same hallway was once lined with display cases, which tempted commuters with handbags, jewelry, and perfumes.

The shopping emporium occupied an entire block between Fulton, Elm, Bond, and Livingston Streets from 1887 to 1952. The building was outfitted with modern luxuries like electric lights, telephone services, elevators, and escalators. Loeser’s sold everything from clothes to pianos. The company even provided the china that was used at Ellis Island! Though Loeser’s went bankrupt in 1952, the decorative subway tiles remain to this day.

9. There is a historic door on the Times Square shuttle platform

Hundreds of thousands of commuters pass through the Times Square/42nd Street station everyday, but the peculiar door at the end of the S shuttle platform remains largely overlooked. The only clue into the door’s secret past is the faded plaque that says “KNICKERBOCKER” on top.

In 1906, John Jacob Astor IV opened the Knickerbocker Hotel on the southeast corner of 42nd Street and Broadway. At the time, it was one of the grandest hotels in the city. It had 15-stories, 600 rooms, a barber shop, a 500-person banquet hall, and an intricate Beaux-Arts facade. In addition, the hotel had a direct entrance from the downtown platform of the new IRT subway line. According to a 1906 New York Times article, the hallway leading to the platform was “furnished with settees and decorated with heraldic banners."

In the early 1900s, the hotel bar was one of the most sophisticated and elegant drinking spots in New York City, attracting the likes of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Enrico Caruso. In fact, the sale of Babe Ruth from the Red Sox to the Yankees took place at the Knickerbocker Hotel!

Its genteel clientele and luxurious ornamentation prompted regular revelers to nickname the bar the “42nd Street Country Club.” The Knickerbocker Hotel’s bar is also believed to be the birthplace of the Martini. The bartender Martini di Arma di Taggia is rumored to have created his namesake cocktail in 1912 for one of the richest men in the world: John D. Rockefeller.

In 1912, John Jacob Astor IV died on the Titanic and his son Vincent Astor inherited the hotel. The hotel remained popular until prohibition was enacted in 1919. The ban on booze hit the hotel hard, prompting Vincent to convert it into offices in 1920. Finally, in 2015, a second Knickerbocker Hotel was opened in the historic building. Sadly, the management has decided to not reopen the hotel’s old subway entrance.

10. Champagne was once served on the subway

In 1962, the MTA installed a champagne car on the subway running between Times Square and South Ferry to publicize a clean up campaign. The “dream car” as it was known also featured plush carpeting, curtains, and flowers. We can only hope that the MTA includes the return of champagne cars in its future infrastructure repair plans — that’s a fare increase I can get behind!